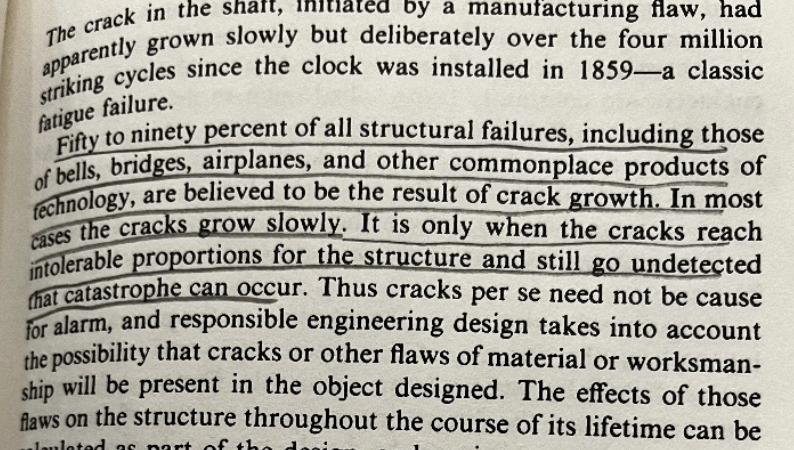

I was reading the "To Engineer Is Human" by Henry Petroski where he argues that failure is not an anomaly, it is the very fabric of the engineering progress. In structural engineering, a catastrophe is rarely a sudden event, most of the times is the result of failure by fatigue: a process where "manufacturing flaws" or tiny microscopic cracks grow slowly until a breaking point.

In the software engineering world these microscopic cracks can be API calls that increase slowly, database queries that start getting slower, interactions by some users that are not anticipated. One bad line of code usually doesnt break the system but many small invisible "cracks" that accumulate overtime until they reach intolerable proportions do.

We can be very strict and try to prevent these "cracks" following the principle of not allowing Broken Windows but we know that this is practically impossible, first because you have deadlines to meet, second because it is very expensive and third because there are many unknown unknowns that you only discover under real conditions and not in a "Lab" environment.

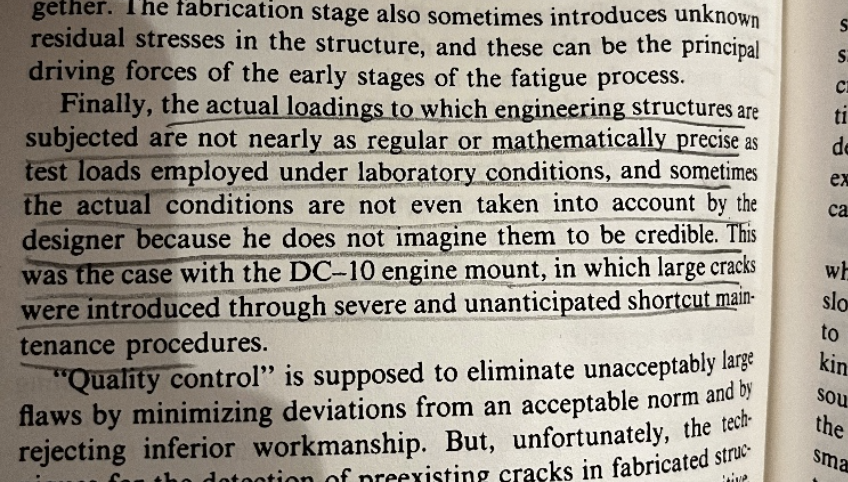

We write automated test, we do performance tests, we do manual test, some lucky ones have QA engineers in their teams, but the truth is that is almost impossible to predict how a system will behave under real conditions. Despite our automated suites and performance benchmarks, we are often just testing for the expected. The real danger isn't the bug we can replicate in staging, it’s the slow, invisible fatigue that only emerges under real conditions. We treat systems as static, but production is a living environment that reveals flaws no test suite could ever predict.

This realization changes the way we must view our craft. If "all machine and structural designs are problems in fatigue," then software engineering is less about achieving a state of static perfection and more about the constant management of decay. The forces of nature (which in software look like shifting requirements, evolving security threats, and scaling demands) are always there. The goal is not to build something that will never break, but to build something where the "cracks" are visible enough to be monitored and managed before they lead to a brittle fracture. We have the tooling for that either is called Grafana, Sentry or Datadog.

People make mistakes, the things we build will have flaws, too. Accepting this doesn't mean we should be careless. Instead, it means we must be even more careful. When we realize that software is a living thing, prone to the same wear and tear as an old clock or a steel bridge, we can stop being afraid of failure. We can start using those small cracks and lessons as the very tools we need to build something that actually lasts.

Nassim Taleb introduced the concept of Antifragility, describing systems that do not just resist cracks but actually get better because of them. In the software engineering world, we see this through Postmortems, where we discuss how to improve existing issues after a production problem is revealed. It takes the form of Runbooks created to solve emergencies, or Chaos Engineering techniques used so we don't have to wait for time to reveal the cracks. It can even be Error Budgets: if you have a high budget left, you take more risks and ship faster; if the budget is low, you focus purely on reliability. This creates a self-healing loop where the "stress" of system instability forces the team to prioritize quality, making the system stronger for the next cycle.

Ultimately, engineering is not about the absence of failure, but the mastery of it. By accepting that software is subject to "fatigue" just like any physical bridge, we shift our focus from the impossible goal of perfection to the vital work of visibility and adaptation.